Narrowing In: Cooling Molecules With Light Like Never Before

January 14, 2026 -- Atoms have long been the cornerstone of laser cooling experiments. Their relatively simple structure makes them straightforward to cool with light, allowing scientists to achieve temperatures near absolute zero. Molecules, by contrast, present a much more formidable challenge. With complex rotational, vibrational, and electronic states, they’re significantly harder to tame.

Now, in a study published in Physical Review X Quantum, a team led by JILA and NIST Fellow and University of Colorado Boulder physics professor Jun Ye has demonstrated—for the first time—narrowline laser cooling of a molecule. By utilizing a previously unaddressed transition in the diatomic molecule yttrium monoxide (YO), the researchers have developed a new approach to manipulate internal states and molecular motion with unprecedented precision.

The advance not only redefines the quantum state control available to laser-cooled molecules, but also lays the foundation for future advancements in quantum simulation, precision measurement, and the potential development of a molecular clock.

From Nuisance to Narrowline

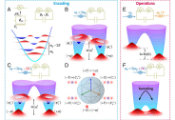

This research relies on a unique property of the yttrium monoxide (YO) molecule: the existence of a long-lived excited electronic state. The longer natural lifetime an excited state possesses, the narrower its transition linewidth is. And these extraordinarily narrow features enable unparalleled spectroscopic precision and can be used to cool molecules below currently achievable temperatures.

It is worth noting that although the long-lived excited state in YO offers immense potential, until recently, it had only provided additional challenges. “If anything, I would say this excited state has historically been a nuisance to laser cooling,” says JILA graduate student Kameron Mehling, the paper’s first author. “Its very presence forced us to modify the already complicated photon cycling schemes necessary to cool YO to begin with.”

Nevertheless, the JILA team has finally harnessed the long-lived electronic state in YO, more than a decade after the idea was initially proposed. By precisely addressing the narrow transition with an ultra-stable laser, they were able to slow down the motion of the molecules (cooling them) via the newly addressed excited state.

Molecules can be cooled with laser light by continuously scattering photons — a technique where matter repeatedly absorbs and emits photons over and over, removing energy and entropy in the process. While this technique has become commonplace for atoms, molecules are trickier due to their extra complexity: they rotate, vibrate, and possess close-lying opposite parity states, making it hard to keep the cycle going.

“This excited state has been continuously occupied as a decay pathway within our previously implemented cycling schemes,” Mehling explains. “However, this is the first time that we’re directly exciting it and exploring the resulting physics.”

The team’s results rely on one of the most accurate spectroscopic measurements ever made in a laser-cooled molecule—resolving the narrowline transition frequency to 11 digits of precision. This highlights the potential of narrowline transitions in laser-cooled molecules for future precision experiments and opened the door for laser cooling.

Expanding the Molecular Control Toolbox

To make narrowline laser cooling practical, the team had to address a longstanding challenge: preventing the molecules from leaking out of the cooling cycle. Their solution came from an unexpected but powerful source—an applied electric field.

In YO, certain energy states come in nearly identical pairs of opposite parity—like twins (think Kameron and Kendall Mehling) with mirrored personalities. It might seem subtle, but mixing up the twins opens unwanted photon “communication” channels and jeopardizes the photon cycling scheme. However, by applying a small electric field, the researchers could identify and isolate a single metastable excited state (i.e. twin) which the laser could repeatedly interact with.

“You have to use another tool in the toolbox,” says JILA postdoctoral researcher Simon Scheidegger.

“Usually in atomic experiments, researchers use light and magnetic fields. But for this, we had to bring in electric fields to isolate the states we care about.”

And the amount of electric field needed? Surprisingly small!

“Other molecular experiments might need 10 to 20 kilovolts per centimeter to observe a similar effect” notes Scheidegger. “We apply fields four orders of magnitude smaller, requiring less voltage than what’s in a AA battery.”

Cooling on the Fly

To demonstrate laser cooling, the team prepared a cloud of ultracold YO molecules and let them fall freely under gravity. While the molecules dropped, they were exposed to carefully tuned laser light and their change in temperature was recorded as the laser frequency was varied.

Despite a brief interaction window, the results were clear: the technique cooled the molecules by a small but significant amount. “Currently we’re limited by how many photons we can scatter off the molecules,” says JILA postdoctoral researcher Logan Hillberry. “Nevertheless, at ultralow temperatures, you are fighting for every additional cooling photon.” The fact laser cooling was demonstrated with only a handful of photons per molecule is particularly impressive —a testament to the technique's efficiency!

“This initial laser cooling demonstration proves we can implement a photon cycling scheme on our narrowline transition, however, there is still plenty of work to be done” says Mengjie Chen, another graduate student on the project. “Since our molecular structure is very well understood, we know we could greatly enhance the cooling effect with only a couple more laser tones.” These future upgrades, along with incorporating the narrowline laser cooling scheme while molecules are trapped in an optical potential, would help initialize record phase space densities and reach currently inaccessible temperatures.

How a Narrow Transition Unlocks Broad Applications

These results suggest more than just a technical milestone— it is a “planting the flag” moment, as the team put it. Narrowline transitions have enabled some of our most precise experiments, like atomic clocks and ongoing searches for fundamental physics. Extending that precision to molecules will unlock entirely new physics. Beyond just laser cooling, the team envisions broad applications across quantum simulation and precision measurements —where molecules are suited to outperform laser-cooled atoms due to their strong electric dipoles. “We’ve built the platform. We’ve demonstrated the tools,” says Mehling. “Now the sky’s the limit.”