Scientists Capture First-Ever High-Resolution Images of Topological Quantum Hall Edge States

January 08, 2026 -- Physicists have long known that some materials behave strangely at their edges, conducting electricity without resistance even as their interiors remain insulating. These boundary phenomena, called topological edge states, form the basis of quantum technologies and exotic “topological phases” of matter. But despite decades of study, scientists could only infer how these quantum edges behave—no one had actually seen their microscopic structure in action.

Now, a collaborative team of researchers have achieved a remarkable first: they directly imaged the internal structure of these edge states in monolayer graphene, using one of the most precise tools in modern physics—scanning tunneling microscopy (STM). Their results, published last week in Nature, reveal how fundamental interactions between electrons reshape the very edge of a quantum material, upending long-held theoretical assumptions and opening a new window onto quantum topological behavior.

“For the last 20 to 30 years, the study of these edge channels has essentially been limited to making hypotheses about how electrons are flowing,” said Ali Yazdani, the James S. McDonnell Distinguished University Professor at Princeton, whose team has applied their powerful quantum microscopy technique to the problem. “Researchers then measure only global properties of the material and say, ‘Oh, this must be what’s happening at the edge,’ piecing together a kind of story about it.”

“People have tried to use microscopy to image these edge channels before,” Yazdani added. “But those earlier efforts suffered from a key limitation: the available microscopy techniques were too blunt, with insufficient spatial resolution to really resolve what was happening at the edge.”

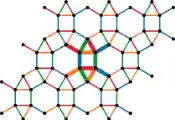

In a quantum Hall system—a sheet of electrons chilled to near absolute zero and immersed in a strong magnetic field—electrons organize into quantized, or discrete, energy levels called Landau levels. The bulk of the material becomes an electrical insulator, but its edges host slim, one-way highways for electrons known as edge channels. These edge channels are the source of the precisely quantized conductance that earned physicists the 1985 Nobel Prize.

Until now, however, scientists couldn’t determine exactly how these edge channels arrange themselves, especially when strong electron–electron interactions come into play. Traditional experiments could only measure global properties like conductance, which is the measure of how easily electric current flows through a material. The dynamics of the local, nanometer-scale structure of the edge itself remained a mystery. And any roughness or disorder at the boundaries blurred the picture even more.

The new study changes that. The research team, based at institutions including Princeton University, UC Berkeley, and UC Santa Barbara, overcame these challenges by combining two key elements: pristine graphene devices and a highly sensitive, non-invasive STM technique.

Graphene provides an ideal platform because its unique electronic structure produces strong electron-electron interactions. “It’s just one atomic layer of carbon atoms thick, so we can effectively confine electrons to two dimensions,” said Kristina Wolinski, a graduate student in Princeton’s Department of Physics and one of the paper’s lead authors. “It’s also an exceptionally clean system with all the ingredients needed to measure the quantum Hall effect and study edge states.”

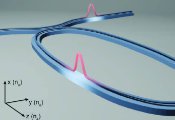

The second breakthrough came when the researchers used new techniques to create the edge of a topological state not at the physical edge of the material, but at an electrically controllable edge.

“So instead of cutting the graphene to make a physical edge, we made an electrostatically defined edge,” said Yazdani. “The advantage is that it can be made exceptionally clean, free from the defects that plague physical edges.”

The researchers then used STM—a technique that scans a sharp metal tip over a surface to map its electronic states atom by atom—to observe how the edge states of quantum Hall phases form, shift, and even reconstruct under the influence of quantum correlations.

“By combining these technical capabilities, we were able to image these edge states with the highest precision to date—something researchers have aimed to do for decades but never achieved,” said Jiachen Yu, the lead author of the paper and a postdoctoral research associate in Princeton’s Department of Physics.

Normally, simple models predict smooth, non-interacting edge channels. Instead, the STM images showed something unexpected: narrow zones—only about 13–15 nanometers wide—where multiple distinct edge channels appeared, each separated cleanly in space. Even more striking, their speed—how quickly disturbances propagate along the edge—was four times higher than theories predicted.

“Our images provided important information about how those channels talk to one another because it’s not just a matter of how many channels you have,” said Yazdani. “It’s how they arrange themselves and how they interact with each other determines their spatial structure. And before this experiment, theory couldn’t even tell you how they would arrange themselves because this is an interacting problem.”

In essence, this work offers the first microscopic confirmation that the edges of topological materials are not merely passive boundaries—they are complex, dynamic regions where quantum correlations play out in unexpected ways. By combining clean graphene engineering with atomic-scale imaging, the researchers turned a decades-old theoretical concept into visual evidence.

The implications of this research are profound. Quantum Hall edge states are not just a theoretical curiosity; they play a crucial role in probing the bulk properties of topological materials and are central to emerging technologies like quantum computing. The ability to visualize and manipulate these edge states opens up new possibilities for designing quantum devices that leverage their unique properties for information processing and storage.

“Scientists have grown increasingly interested in these edge states because they may be the basis of new quantum devices—type of qubits—for quantum information processing,” said Yu. “These devices rely on edge states to store, manipulate, and transmit quantum information.”

Overall, this study represents a significant leap forward in the field of quantum materials and demonstrates the power of advanced imaging techniques like STM in unraveling the mysteries of the quantum world. As researchers continue to push the boundaries of what is possible, the insights gained from this work could pave the way for transformative technologies and deepen our understanding of the fundamental principles governing the universe.

Looking ahead, the researchers intend to expand their technique to probe even more exotic states—such as quantum Hall phases in which electrons fractionalize into more exotic particles. This is an exciting new frontier in condensed matter physics that promises to help shed light on how collective electron behavior gives rise to emergent quasiparticles and topological phases that have no counterpart in ordinary materials.

The study, “Visualizing interaction-driven restructuring of topologicak quantum Hall edge states,” by Jiachen Yu, Haotan Han, Kristina Wolinski, Ruihua Fan, Amir Mohammadi, Tianle Wang, Taige Wang, Liam Cohen, Kenji Watanabe, Takashi Taniguchi, Andrea F. Young, Michael P. Zaletel, and Ali Yazdani, was published on December 17, 2025 in the journal Nature.