Realising Quantum Advantage in Analogue Quantum Simulation

February 02, 2026 -- A major research programme launched in October 2024 is tackling the big question in quantum computing and related areas: when will quantum systems deliver a practical advantage for problems that matter to science or industry? The Quantum Advantage in Quantitative Quantum Simulation programme is led by the University of Oxford and funded by UK Research and Innovation; it is advancing a different and increasingly powerful approach to the question – not by building ever larger digital quantum computers, but also through analogue quantum simulation. These highly controlled devices can be used to implement and study models of other quantum systems.

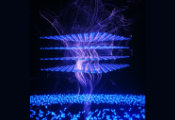

Rather than performing general-purpose computations, analogue quantum simulators are carefully engineered quantum systems designed to mimic the behaviour of other, less accessible quantum materials and processes. In this sense, they are closer to analogue computers (or to wind tunnels for aerodynamics) than to conventional digital computers. Crucially, analogue simulators may reach practical usefulness sooner, though for a more focused class of problems, than fully fault-tolerant digital quantum computers. For specific tasks – especially relevant to underpinning science in materials, they may even outperform digital approaches altogether. And they also provide a new set of tools for quantum enhanced sensing and metrology.

Exploiting quantum advantage

The EPSRC programme grant brings together experimental and theoretical researchers with a shared goal: to demonstrate, verify, and exploit quantum advantage in analogue quantum simulators for well-defined classes of quantum dynamics. The experimental platforms at the heart of the programme use large arrays of neutral atoms, held and controlled by precisely structured laser light in optical lattices and optical tweezers. With more than 150 atoms (and up to 10000) arranged in configurable geometries, these systems represent some of the most advanced analogue quantum simulators currently available. A distinguishing feature of this programme is its emphasis on quantitative simulation. Rather than simply observing interesting quantum behaviour, the aim is to establish regimes where these devices can be shown – rigorously and convincingly – to outperform any known classical method for predicting the same dynamics.

The programme hosted a three-day workshop at Keble College, Oxford last month with the meeting serving as the programme’s annual review, while also drawing in leading international experts working with neutral atoms and related platforms. Across invited talks, contributed presentations, and poster sessions, the workshop explored how controlled atomic systems can be used to study complex many-body physics, including phenomena relevant to materials science, quantum metrology, and sensing. Topics ranged from atoms arranged in optical lattices and tweezer arrays, to dipolar quantum gases, confined atomic systems, and quantum dynamics in topological, disordered, and quasicrystalline structures. A recurring theme was the question of what it really takes to claim quantum advantage – how experimental results can be meaningfully compared with the best available classical simulations, and how they might be exploited also in measurement and sensing.

The groundwork for future breakthroughs

‘The long-term vision of the programme is transformative,’ comments Professor Andrew Daley, the programme’s principal investigator. ‘We want to help turn analogue quantum simulators from specialist laboratory tools into platforms that are genuinely useful beyond basic science. This will come both directly through simulation of quantum dynamics that underpins new materials, and in the development of new techniques for sensors and atomic clocks. As quantum technologies continue to evolve, analogue quantum simulators offer a compelling and pragmatic route to new applications with different kinds of quantum advantage – our work is building on what is already possible today, and laying the groundwork for future breakthroughs.’