Atomic Nucleus Excited With Laser: A Breakthrough After Decades

Physicists have been hoping for this moment for a long time: for many years, scientists all around the world have been searching for a very specific state of thorium atomic nuclei that promises revolutionary technological applications. It could be used, for example, to build an nuclear clock that could measure time more precisely than the best atomic clocks available today. It could also be used to answer completely new fundamental questions in physics - for example, the question of whether the constants of nature are actually constant or whether they change in space and time.

Now this hope has come true: the long-sought thorium transition has been found, its energy is now known exactly. For the first time, it has been possible to use a laser to transfer an atomic nucleus into a state of higher energy and then precisely track its return to its original state. This makes it possible to combine two areas of physics that previously had little to do with each other: classical quantum physics and nuclear physics. A crucial prerequisite for this success was the development of special thorium-containing crystals. A research team led by Prof. Thorsten Schumm from TU Wien (Vienna) has now published this success together with a team from the National Metrology Institute Braunschweig (PTB) in the journal "Physical Review Letters".

Switching quantum states

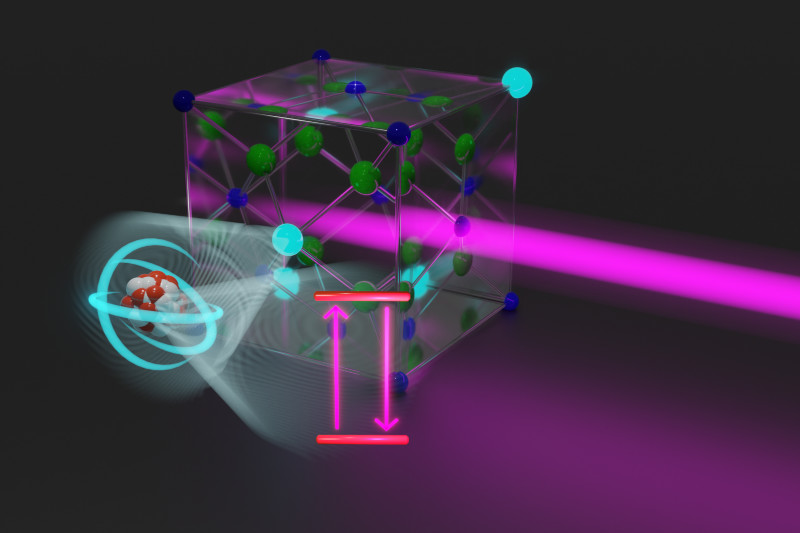

Manipulating atoms or molecules with lasers is commonplace today: if the wavelength of the laser is chosen exactly right, atoms or molecules can be switched from one state to another. In this way, the energies of atoms or molecules can be measured very precisely. Many precision measurement techniques are based on this, such as today's atomic clocks, but also chemical analysis methods. Lasers are also often used in quantum computers to store information in atoms or molecules.

For a long time, however, it seemed impossible to apply these techniques to atomic nuclei. "Atomic nuclei can also switch between different quantum states. However, it usually takes much more energy to change an atomic nucleus from one state to another – at least a thousand times the energy of electrons in an atom or a molecule," says Thorsten Schumm. "This is why normally atomic nuclei cannot be manipulated with lasers. The energy of the photons is simply not enough."

This is unfortunate, because atomic nuclei are actually the perfect quantum objects for precision measurements: They are much smaller than atoms and molecules and are therefore much less susceptible to external disturbances, such as electromagnetic fields. In principle, they would therefore allow measurements with unprecedented accuracy.

The needle in the haystack

Since the 1970s, there has been speculation that there might be a special atomic nucleus which, unlike other nuclei, could perhaps be manipulated with a laser, namely thorium-229. This nucleus has two very closely adjacent energy states – so closely adjacent that a laser should in principle be sufficient to change the state of the atomic nucleus.

For a long time, however, there was only indirect evidence of the existence of this transition. "The problem is that you have to know the energy of the transition extremely precisely in order to be able to induce the transition with a laser beam," says Thorsten Schumm. "Knowing the energy of this transition to within one electron volt is of little use, if you have to hit the right energy with a precision of one millionth of an electron volt in order to detect the transition.” It is like looking for a needle in a haystack – or trying to find a small treasure chest buried on a kilometer-long island.

The thorium crystal trick

Some research groups have tried to study thorium nuclei by holding them individually in place in electromagnetic traps. However, Thorsten Schumm and his team chose a completely different technique. "We developed crystals in which large numbers of thorium atoms are incorporated," explains Fabian Schaden, who developed the crystals in Vienna and measured them together with the PTB team. "Although this is technically quite complex, it has the advantage that we can not only study individual thorium nuclei in this way but can hit approximately ten to the power of seventeen thorium nuclei simultaneously with the laser – about a million times more than there are stars in our galaxy." The large number of thorium nuclei amplifies the effect, shortens the required measurement time and increases the probability of actually finding the energy transition.

On November 21, 2023, the team was finally successful: the correct energy of the thorium transition was hit exactly, the thorium nuclei delivered a clear signal for the first time. The laser beam had actually switched their state. After careful examination and evaluation of the data, the result has now been published.

"For us, this is a dream coming true," says Thorsten Schumm. Since 2009, Schumm had focused his research entirely on the search for the thorium transition. His group as well as competing teams from all over the world have repeatedly achieved important partial successes in recent years. "Of course we are delighted that we are now the ones who can present the crucial breakthrough: The first targeted laser excitation of an atomic nucleus," says Schumm.

The dream of the atomic nucleus clock

This marks the start of a new exciting era of research: now that the team knows how to excite the thorium state, this technology can be used for precision measurements. "From the very beginning, building an atomic clock was an important long-term goal," says Thorsten Schumm. "Similar to how a pendulum clock uses the swinging of the pendulum as a timer, the oscillation of the light that excites the thorium transition could be used as a timer for a new type of clock that would be significantly more accurate than the best atomic clocks available today."

But it is not just time that could be measured much more precisely in this way than before. For example, the Earth's gravitational field could be analyzed so precisely that it could provide indications of mineral resources or earthquakes. The measurement method could also be used to get to the bottom of fundamental mysteries of physics: Are the constants of nature really constant? Or can tiny changes perhaps be measured over time? "Our measuring method is just the beginning," says Thorsten Schumm. "We cannot yet predict what results we will achieve with it. It will certainly be very exciting."