Monash Researchers Reveal Atomic Structure at Gold Nanoparticle Interfaces

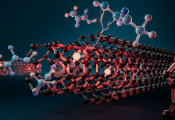

February 04, 2026 -- A Monash University team has achieved a major advance in nanoscience by directly determining the atomic structure at the hard–soft interface of gold nanoparticles, a region long considered too delicate and too complex to image with certainty.

The work, published in Nature Communications, resolves a fundamental barrier in understanding how metal nanocrystals grow, change shape and interact with their chemical environment.

Using a specially developed method based on four‑dimensional scanning transmission electron microscopy (4D‑STEM), the researchers were able to visualise and distinguish gold atoms, copper additives and bromide counterions at the surface of gold nanocuboids grown in the presence of a surfactant.

By tailoring the imaging conditions to be preferentially sensitive to these surface species, the team were able to measure interatomic distances and reconstruct the atomic arrangement at the interface with unprecedented clarity.

Dr Weilun Li from the Monash University School of Physics and Astronomy, who was lead author of the study, said the breakthrough addresses a long‑standing gap in nanomaterials research.

“For years, we have known that additives and surfactants control how nanocrystals grow, but the atomic structure at the interface has remained hidden,” Dr Li said.

“The challenge is that these surface atoms produce extremely weak signals, and conventional imaging methods either damage the surfactant or cannot distinguish the different species.”

The team’s approach overcomes these limitations by using electron‑scattering calculations to identify specific angular ranges where copper and bromide scatter more strongly than gold. By reconstructing images from only these regions of the 4D‑STEM dataset, the researchers produced directly interpretable maps of the surface adatoms and counterions without the ambiguities that have plagued earlier techniques.

“This method allowed us to see the copper additives and bromide ions at the gold surface while keeping the surfactant layer intact,” Dr Li said. “From these images, we could measure the interatomic distances and determine the atomic structure of the hard–soft interface. To the best of our knowledge, this structure has not been measured previously in any nanoparticle system.”

The findings provide the atomic‑level information needed to understand how additives modify surface energies, how surfactants bind to specific facets and why certain nanocrystal shapes emerge during growth. The authors note that the same general imaging strategy can be applied to other nanoparticle systems with different additives or surfactants.

Dr Li said the work opens new possibilities for rational design of nanomaterials. “By revealing how these atoms are arranged at the surface, we can start to build accurate models of growth mechanisms and surface chemistry,” he said. “This is essential for controlling nanocrystal morphology and for improving their performance in applications ranging from catalysis to photonics.”

The study demonstrates that low‑dose, species‑sensitive 4D‑STEM can finally resolve the atomic structure at nanoparticle additive–surfactant interfaces, a region that has remained experimentally inaccessible despite decades of effort.