New Role Discovered for Contextuality in Quantum Error Correction

January 30, 2026 -- A major challenge in quantum computing is dealing with errors that creep in during computations. Researchers from the Centre for Quantum Technologies (CQT) and the Agency for Science, Technology and Research (A*STAR) have found that some of the most powerful error correction codes might have one thing in common: contextuality.

Contextuality is a fundamental property of quantum physics. When a quantum system exhibits contextuality, the outcome of one measurement depends on the other measurements performed alongside it – that is, their context.

The property of contextuality has already been used in device certification, machine learning and quantum communication. It was also known to have a role in one class of error correction codes that use ‘magic states’.

Now, co-authors CQT PhD student Andrew Tanggara and A*STAR’s Derek Khu, Chao Jin and Kishor Bharti, a CQT PhD graduate, have discovered that contextuality is also a necessary feature for error correction that uses ‘code-switching’ to achieve fault tolerant computation. They say it could be a powerful ‘litmus test’ – if a proposed error correcting scheme is not contextual, it cannot be used to achieve universality. Their work was published 28 January 2026 in PRX Quantum.

“For decades, contextuality largely occupied the ‘why quantum mechanics is strange’ corner of physics. It is now steadily migrating into the domain of ‘how to build tools with quantum mechanics.’ The work of Khu and his colleagues advances this transition by linking contextuality directly to the structure of practical fault-tolerant codes rather than to idealized state-based models of quantum information processing,” write the authors of an expert Viewpoint published in Physics magazine about the paper.

Local consistency, global inconsistency

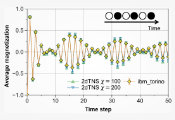

Error correction was big news in quantum computing in 2025, with a slew of results from companies and research groups making progress towards fault tolerant, or universal, computing.

Quantum error correction protects against noise by adding redundancy – one qubit of information is stored across many physical qubits. Error correction codes are a set of measurements performed on these physical qubits.

Contextuality can manifest in these measurement outcomes. Take for example a code that has three measurements, M1, M2 and M3. If the code was non-contextual, the values of the measurements would always be the same regardless of the order of the measurements. This could mean for instance that M1 is 0, M2 is 1 and M3 is 1. In contrast, if the code was contextual, measuring M1, M2 then M3 would still give 0, 1, 1, but measuring M3, M2 then M1 might give 0, 0,1.

Andrew says, “For a contextual code, there is a ‘context’ which is going to cause some global inconsistencies, even though it is always the case that local consistency is satisfied.” The local consistency may be relationships among subsets of measurements.

The researchers draw an analogy to the Penrose steps, an optical illusion showing four flights of steps arranged in a square. Any two or three flights viewed together look like they go up, but change the context to view them altogether and you find an inconsistency – they seemingly end up at the same level.

Small blankets

It is known in error correction that no single code can fix everything by itself. This was proved mathematically by what is known as the ‘Eastin-Knill theorem’. The researchers highlight an analogy by CQT Founding Director Artur Ekert: You can think of an error correction code as a blanket that is too small – using the blanket to cover your shoulders leaves your feet cold, and vice versa. The theorem says that in quantum error correction no single blanket is large enough.

To overcome this limitation, you can use ‘code-switching’ – something like stitching your blankets together into a patchwork quilt – but the switching has to be done properly or the quantum information will be exposed to noise and destroyed.

“The theorem only tells us one code is not enough. It does not tell us which codes to use together,” says Derek, who is also the first author of the paper. “What we found is that maybe we need to look at contextuality.”

Checking all the code-switching protocols they knew of, they discovered that those that can overcome the Eastin-Knill theorem are contextual. This means that the collective measurement outcomes of the different error correction codes used must exhibit contextuality. If the codes have measurement outcomes that are collectively non-contextual, they find the Eastin-Knill theorem cannot be overcome.

Inspired by this discovery, the researchers want to further investigate the role of contextuality in fault tolerant computing.