Argonne Launches Silicon Quantum Processor Collaboration With Intel

January 06, 2026 -- In the mid-1900s, a device called the transistor came on the scene, sparking a revolution. Small and efficient, it took the place of the vacuum tube — the large, power-hungry component that once dominated computers. It’s thanks to transistors that computers can now fit in pockets and that pacemakers can be implanted in human hearts.

Transistors control the flow of electrical current. They amplify the current coming through an antenna so you can hear the radio. They switch the current on and off billions of times per second so your computer can perform calculations.

Over the decades, engineers have pushed the transistor to manipulate electrons with ever greater finesse. Now transistors are so advanced, they can flip the tiniest switch of all — the quantum spin of a single electron — to carry information, just like earlier transistors did with electric current.

In short, the transistor evolved into a new species: a quantum dot.

“What if we do at a single-electron level what transistors already do? What if we make quantum technology out of the same building blocks that we already make classical technology out of?” said Jonathan Marcks, a scientist at the U.S. Department of Energy’s (DOE) Argonne National Laboratory, who leads the effort. “You can draw a very direct line from the first transistor to a quantum dot.”

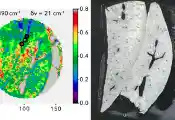

Now Argonne has successfully deployed and is running a 12-qubit quantum dot device built by Intel, with the first collaborative work published in Nature Communications. (Qubits are the carriers of quantum information.) Led by Q-NEXT, a DOE National Quantum Information Science Research Center hosted by Argonne, the project builds on decades of expertise in silicon transistor manufacturing to advance quantum dot technology.

“This collaboration between Argonne and Intel is a cornerstone of Q-NEXT,” said Q-NEXT Inaugural Director David Awschalom, who is a senior scientist at Argonne, the Liew Family professor and director of the Chicago Quantum Institute at the University of Chicago Pritzker School for Molecular Engineering and the founding director of the Chicago Quantum Exchange. “It shows the impact of a national quantum research center: Only at this scale can industry and discovery-driven organizations like the national laboratories combine their strengths to build such a complex system. Together, we accomplish advances that would be challenging for a single investigator, or even a single institution, to achieve alone.”

In building quantum dot qubits, scientists leverage advanced transistor manufacturing processes for a quantum future.

What’s a quantum dot?

A dot-sized lesson in quantum physics: All particles — molecules, atoms, electrons — have a wavelength.

Quantum dots confine these particles to a space smaller than their wavelength. Because of the rules of quantum physics, this confinement forces the particles into discrete, tunable energy levels, like the rungs of a ladder. By adjusting the dots’ size and composition, scientists can control the energy levels precisely.

Having scaled information down to the level of a quantum dot — to a single-electron transistor — researchers are now working to scale up these spin qubits for use in quantum computers and other technologies, engineering them to precise specifications. In principle, quantum dot qubits could be tuned one way to sense disease in human tissue and another way to calculate the best cross-country route for truck deliveries.

“We’re accelerating research by getting over one of the really big hurdles to doing this work. It can be difficult to build even a few quantum dot qubits,” Marcks said. “But with Intel, the prospect of making a ton of qubits on a practical device using quantum dots suddenly seems a lot more realistic.”

Intel provides the capabilities for building and manufacturing high-tech devices. Argonne provides expertise to put Intel’s quantum dot qubits through their paces.

“There’s a good match between Intel’s manufactured devices and our open-science approach, figuring out the appropriate questions to ask,” Marcks said. “Together, we’ll be able to scale up the number of qubits to a point that’s relevant for quantum computing.”

Lots of dots

And that requires a lot of quantum dots.

“To do complicated quantum information processing, to do something useful with these devices, you need hundreds, thousands, millions of qubits. That scaling is difficult,” Marcks said.

“We are eager to continue work with Q-NEXT as we scale to hundreds of dots,” said Nathan Bishop, quantum systems technology director at Intel. “Intel’s design, fabrication and test teams make it possible to scale up quantum processors based on silicon quantum dot qubits. By working with scientists at Argonne, we enable cutting-edge science and benefit from DOE’s world-class capability for materials and qubit characterization.”

Argonne is helping with the scale-up by investigating the features of Intel’s 12-dot system. What is the best way to wrangle these qubits to work together? What happens as you make the system larger? How do different material properties affect the quantum dots’ operation?

“How these qubits behave together requires a lot of physics research and insight, so we’re conducting experiments to see what’s possible,” Marcks said. “And that’s where Argonne excels. There’s a lot of exploratory science to be done that can feed back into engineering better devices.”

Argonne’s feedback to Intel will help the development of progressively larger quantum dot systems, which in turn can be installed at Argonne for more tests and exploration, taking the creation of semiconducting devices to the quantum limit.

“Argonne and the national labs excel at basic science and understanding how complex systems function. And companies can make high-quality devices,” Marcks said. “As a company, Intel is invested in engineering fully integrated quantum processors that we can study in the lab, and everyone benefits from more research into these systems. You need both partners to ultimately build something useful.”

This work was supported by the DOE Office of Science National Quantum Information Science Research Centers as part of the Q-NEXT center.