UIC Researchers Image Near-Room-Temperature Superconductors

December 19, 2025 -- New research from the University of Illinois Chicago may help scientists move one step closer to developing superconductors that operate in ambient conditions at room temperature and pressure, a long-sought advancement in physics and engineering.

Superconductors are materials that can conduct electricity without resistance, or without losing energy. They’re used in a variety of applications, like MRI machines, magnetic-levitation trains and power transmission. But the materials must be cooled to extremely low temperatures — several hundred degrees below zero Fahrenheit — to work, an expensive and laborious process.

“Superconductivity at ambient conditions would revolutionize how we store, move and use energy,” said Abdul Haseeb Manayil-Marathamkottil, a chemistry PhD student in the lab of Russell Hemley at UIC. “It would eliminate resistive losses, one of the fundamental limits of today’s energy infrastructure, dramatically lowering energy costs.”

In a new study in Nature Communications, Manayil-Marathamkottil, Hemley and co-authors showed how a kind of material called a superhydride acts as a superconductor at near-room temperatures. Using the Advanced Photon Source at Argonne National Laboratory, the world’s most powerful microscope, they uncovered how the crystal structure of this superhydride affects its superconducting behavior.

Superhydrides are novel materials discovered and produced by Hemley’s group. They consist of mostly hydrogen and a small number of metal atoms. Under intense pressure, these superhydrides can conduct electricity with zero resistance. In 2018, the researchers showed that a superhydride called lanthanum decahydride could superconduct at temperatures up to 260 K (around 8 degrees Fahrenheit) — but at extremely high pressures.

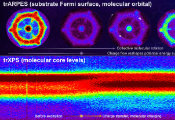

To decrease the amount of pressure required and make the system more stable, in the new study the researchers tried adding a small fraction of another element, the metal yttrium, to the superhydride.

“By adding one more element, we use chemistry to reduce the pressure required in the system and ultimately make it technically usable,” Manayil-Marathamkottil said.

After creating this lanthanum and yttrium superhydride, the scientists studied its structure and behavior at the Advanced Photon Source. They used the facility, which had recently undergone a major upgrade, to shoot high-energy X-rays at the superhydride. This revealed how changing the arrangement of atoms in the material controls its superconducting abilities.

X-ray imaging these crystal structures with unprecedented spatial resolution under pressure, these are among the first experiments to show just how powerful the recently upgraded Advanced Photon Source is as an X-ray microscope, Hemley said. The collaboration between Argonne and UIC through the Chicago/DOE Alliance Center and the National Science Foundation was critical to the work, the researchers said.

The experiments were conducted at pressures measuring down to 136 gigapascals, still an immense amount of pressure (one gigapascal equals the pressure of 10,000 elephants sitting atop a standard pencil), so the team continues to work on studying superconducting hydrides at lower pressures.

For example, the researchers are adding more elements to lower the pressure further and to make these materials practical for real-world use.

“By adding more elements to the mix, we will create new structures,” Hemley said. “We’re going to need very good probes of the structure and composition, such as can be provided by the Advanced Photon Source, to understand these chemically more complex systems exhibiting potential superconductivity at ambient conditions.”