Physicists Use Light to Probe Deeper Into the ‘Invisible’ Energy States of Molecules

July 31, 2024 -- A new optical phenomenon has been demonstrated by an international team of scientists led by physicists at the University of Bath, with significant potential impact in pharmaceutical science, security, forensics, environmental science, art conservation and medicine.

Molecules rotate and vibrate in very specific ways. When light shines on them it bounces and scatters. For every million light particles (photons), a single one changes colour. This change is the Raman effect. Collecting many of these colour-changing photons paints a picture of the energy states of molecules and identifies them.

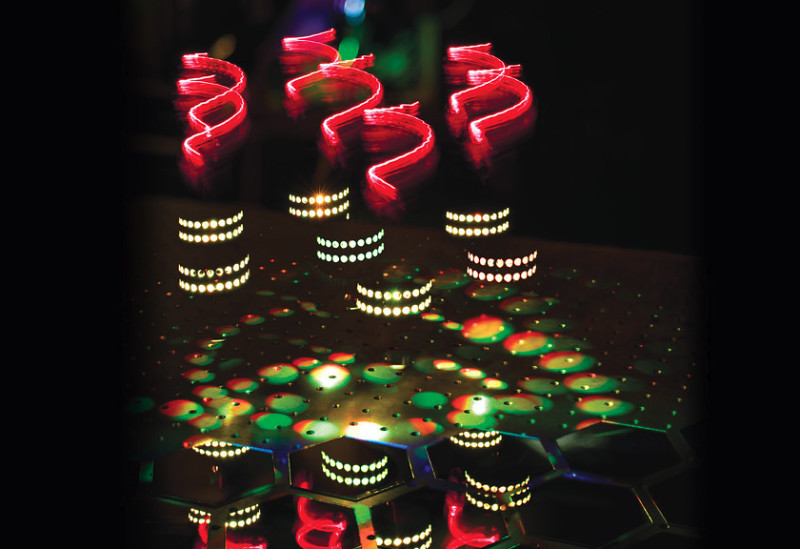

Yet some molecular features (energy states) are invisible to the Raman effect. To reveal them and paint a more complete picture, ‘hyper-Raman’ is needed. The hyper-Raman effect is a more advanced phenomenon than simple Raman. It occurs when two photons impact the molecule simultaneously and then combine to create a single scattered photon that exhibits a Raman colour change.

Hyper-Raman can penetrate deeper into living tissue, it is less likely to damage molecules and it yields images with better contrast (less noise from autofluorescence). Importantly, while the hyper-Raman photons are even fewer than those in the case of Raman, their number can be greatly increased by the presence of tiny metal pieces (nanoparticles) close to the molecule.

Despite its significant advantages, so far hyper-Raman has not been able to study a key enabling property of life – chirality. In molecules, chirality refers to their sense of twist – in many ways similar to the helical structure of DNA. Many bio-molecules exhibit chirality, including proteins, RNA, sugars, amino acids, some vitamins, some steroids and several alkaloids.

Light too can be chiral and in 1979, the researchers David L. Andrews and Thiruiappah Thirunamachandran theorised that chiral light used for the hyper-Raman effect could deliver three-dimensional information about the molecules, to reveal their chirality.

However, this new effect – known as hyper-Raman optical activity – was expected to be very subtle, perhaps even impossible to measure. Experimentalists who failed to observe it struggled with the purity of their chiral light. Moreover, as the effect is very subtle, they tried using large laser powers, but this ended up damaging the molecules being studied.

Explaining, Professor Ventsislav Valev who led both the Bath team and the study, said: “While previous attempts aimed to measure the effect directly from chiral molecules, we took an indirect approach. We employed molecules that are not chiral by themselves, but we made them chiral by assembling them on a chiral scaffold. Specifically, we deposited molecules on tiny gold nanohelices that effectively conferred their twist (chirality) to the molecules. The gold nanohelices have another very significant benefit – they serve as tiny antennas and focus light onto the molecules. This process augments the hyper-Raman signal and helped us to detect it.”

This new effect could serve to analyse the composition of pharmaceuticals and to control their quality. It can help identify the authenticity of products and reveal fakes. It could also serve to identify illegal drugs and explosives at customs or crime scenes.

It will aid detecting pollutants in environmental samples from air, water and soil. It could reveal the composition of pigments in art for conservation and restoration purposes, and it will likely find clinical applications for medical diagnosis by detecting disease-induced molecular changes.

The research is published in the journal Nature Photonics. It was funded by The Royal Society, the Leverhulme Trust, and the Engineering and Physical Science Research Council (EPSRC).